Alex Danchev and Debbie Lisle observed some years ago that ‘many artists are highly sophisticated analysts of the international sphere’ (2009, 775). In our recent article on appropriation as a method for visual analysis of the international, we therefore suggest understanding the scholar as image-maker and the image-maker as scholar (Möller, Bellmer, and Saugmann 2021).

A good example of the image-maker as scholar is Susan Meiselas whose work can currently be seen in the impressive retrospective Susan Meiselas: Mediations at C׀O Berlin (see also Meiselas 2018) covering a 50-year career.

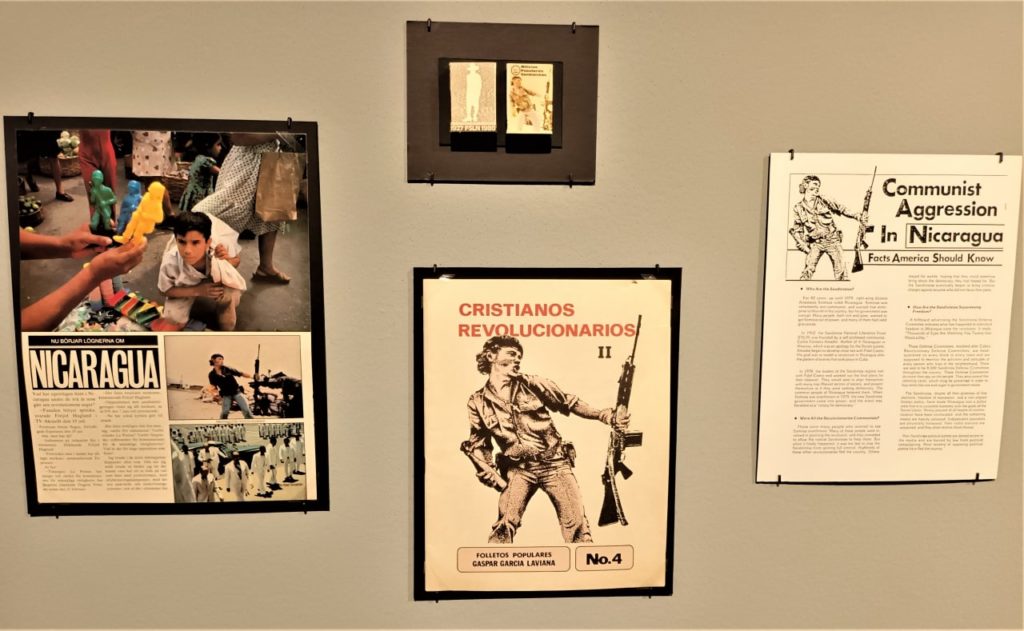

Starting with socially concerned photography in her local neighborhood, Meiselas entered the premier league of photojournalism with her work in Nicaragua (see her 2008 book – a book ‘made so that we remember’) and El Salvador – a female photographer producing color images in a genre dominated by male photographers and black-and-white images; an independent free-lance photographer whose work was nevertheless ‘widely published in the United States as well as internationally’ (Wilkes Tucker and Michels with Zelt 2012, 144).

Meiselas has always been critical of the conventions of photography, photojournalism, and photographic representation. For example, in the exhibition space, viewers are exposed to three layers of images from her work in Nicaragua: the book pages are shown in the middle one, cuttings from magazines including her photographs appear in the upper one, and in the bottom one ‘contact sheets and Xerox copies of individual images offering alternatives to the images selected for the book’ can be seen (Carles Guerra, in Meiselas 2018, 77). The organization of the images invites viewers to navigate them horizontally or vertically, chronologically or randomly, jumping from one layer to another or following more traditional reading patterns. Detached from the way the images appear in the book, new visual narratives can be identified challenging ‘any one-sided interpretations of all the material compiled and ordered by Meiselas’ (Guerra, in Meiselas 2018, 77).

Meiselas also permanently interrogates her relationship as a photographer with the subjects depicted. In the exhibition, she asks: ‘How do you work as a photographer? There’s always this uncomfortable, unequal balance of power. How do you break that down? How can it become a dialog?’ As Pia Viewing suggests (in Meiselas 2018, 11), the process of ‘develop[ing] long-term relationships with many people she photographs … is launched through the identification of a place or a situation and is followed by research on the context.’

Although challenging photojournalistic conventions, Meiselas produced photographs that the photographic discourse elevated to the status of icons, for example the image Sandinistas at the Wall of the National Guard Headquarters: ‘Molotov Man,’ Esteli, Nicaragua, 16 July, 1979. This image and its transformation into an icon can be seen in the exhibition.

Meiselas’s work both anticipates and reconstructs the photographic archive. Even before it is taken, an image can become part of a ‘potential archive in the photographer’s mind,’ as Viewing argues (in Meiselas 2018, 21). For Meiselas, taking a photograph of something or someone implied ‘thinking about that moment when they would no longer be there. The present tense became impossible. I couldn’t shoot because I kept feeling as if holding up my camera was an acknowledgement of the possibility of their death’ (Meiselas 2018, 21).

In her project Kurdistan (1991–2017), inspired, as the exhibition explains, by ‘Saddam Hussein’s Anfal campaign of genocide against the Kurds launched in 1988’ in northern Iraq, Meiselas chose a different approach anticipating, but ultimately dismissing, forensic photography (which is so on vogue nowadays). More than her work in Nicaragua, Kurdistan provides, as Ariella Azoulay suggests (in Meiselas 2018, 99), ‘an opportunity to explore destruction not through its iconic representations by which imperial gestures of destruction are reaffirmed visually, but rather as a terrain of struggle between imperialism’s drive to destroy and a non-imperial commitment to protect threatened worlds and retain them alive.’

With this project, Meiselas explains in the exhibition, she wanted to bear witness through photography ‘to a crime by imaging the exhumation of a mass grave of individual remains.’ Realizing that forensic photography tells us very little about the victim – in particular, it tells us little about who this person was and how she lived before she died – Meiselas decided to combine photographs with videos, documents, and oral accounts to construct an archive of collective memory and with a site-specific story-map from diaspora Kurdish communities. ‘Pictures,’ Meiselas argues, ‘are made and taken away.’ In contrast, she wanted to return pictures, stories, and memories to the Kurdish community, regularly threatened by both physical and cultural annihilation.

The original book project morphed into an online project – akaKurdistan – which, as Işin Önol reports (in Meiselas 2018, 127), ‘has been brutally attacked and hacked many times.’

Combining a book, an online project, workshops, and exhibitions connects the photographer strongly with the communities depicted in her work; her work is work for these communities, not about them. On the one hand, then, Meiselas violates critical distance, neutrality, and objectivity which often appear as core characteristics of photojournalistic work; on the other hand, however, she positions herself in a tradition launched by Robert Capa, Gerda Taro, and David Seymour in which a photographer ‘ha[s] to be engaged, ha[s] to have judged the political stakes in [the] story, and ha[s] to have taken sides’ (Wallis 2010, 13) in order to produce a compelling narrative.

As noted in the exhibition, the presentation of Meiselas’s photographs ‘alongside interviews, sound recordings, videos, archival material, and notes … invite[s] reflection on the photographic practice itself, on bearing witness, on the hierarchies in the photographic act, and on the reception and dissemination of images.’

C׀O Berlin, until 9 September 2022.

References:

Alex Danchev and Debbie Lisle, ‘Introduction: Art, Politics, Purpose,’ Review of International Studies 35:4 (October 2009), 775–779

Frank Möller, Rasmus Bellmer, and Rune Saugmann, ‘Visual Appropriation: A Self-reflexive Qualitative Method for Visual Analysis of the International,’ International Political Sociology (2021), https://doi.org/10.1093/ips/olab029

Susan Meiselas, edited with Claire Rosenberg, Nicaragua: June 1978 – July 1979 (New York: Aperture, 2008)

Susan Meiselas, Mediations (Paris: Jeu de Paume/Barcelona: Fundació Antoni Tàpies/Bologna: Damiani, 2018)

Anne Wilkes Tucker and Will Michels with Natalie Zelt, War/Photography: Images of Armed Conflict and Its Aftermath (Houston: The Museum of Fine Arts/New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2012)

Brian Wallis, ‘Recovering the Mexican Suitcase,’ in The Mexican Suitcase: The Rediscovered Spanish Civil War Negatives of Capa, Chim, and Taro. Volume 1: The History, edited by Cynthia Young (New York: International Center of Photography/Göttingen: Steidl, 2010), pp. 13–17.

https://co-berlin.org/en/program/exhibitions/susan-meiselas