The Galicia Museum, Kraków (permanent exhibition)

Over the last couple of years, we have devoted considerable attention to the merits and liabilities of aftermath photography.

In several publications, we criticized conventional aftermath photography for its tendency to create visual memory bubbles – images revolving around and referring back to the original event without offering escape strategies, thus failing to make the step from aftermath to peace.¹

It is, of course, important to visualize the legacies of the past and to visually engage traumatic reenactments of the past. However, if the past is all there is, then there is no future, no possibility for change. Is it possible, we asked, to conceive of visualizations of the past also as building blocks for the future, perhaps even for peace?

Is it possible, then, to integrate visual representations of a traumatic past in visual narratives that have a forward-looking perspective (in addition to all the good things attributed to conventional aftermath photography)?

In the exhibition Rediscovering Traces of Memory: Contemporary Look at the Jewish Past in Poland, which is permanently on show at the Galicia Museum in Kraków, the organizers have chosen an approach that seems to resonate with our suggestion: memory as an ingredient of, or even a building block for, something new.

As Jonathan Webber explains, instead of presenting a historical or chronological exhibition consisting of black-and-white photographs visualizing the original event and its continuing relevance for the people affected by it, the exhibition’s subject is “the present-day realities” and these realities are “presented in colour. The idea is to show a representative sample of the remains from the Jewish past after the Holocaust and to suggest insights into what they mean,” then and now.

The museum explains on its website that the exhibition tries to evoke “five ways or moods in which the tragic Jewish absence after the Holocaust could be approached: sadness in confronting ruins; interest in the original culture; horror at the process of destruction; and recognition of the problems in coping with the past, including both the erasure of memory and also the efforts to preserve and memorialise the traces of memory.”

Importantly, people appear in the images only in the final section, focusing on some of those “who are involved today, in different ways, in honouring the memory of the Jewish past in Galicia, celebrating its culture and so contributing to the Jewish presence here coming back to life – today’s Jewish revival.” Hence, “ruins as well as restorations, absence as well as presence.”

Equally importantly, by combining photographs taken by Chris Schwarz in the 1990s and photographs taken by Jason Francisco approximately twenty years later, the exhibition visualizes what we would like to call the temporality of the aftermath.² In Webber’s words, the exhibition shows “both the starting-point of how Jewish heritage looked 25 years ago and how it has evolved into what it looks like today.”

Whether or not the people depicted in the final section regard the images as photographs of peace – in other words, whether or not the evolution of Jewish heritage in Galicia can be grasped in terms of a transition from the aftermath to peace – is for them to decide, not for us.

We would like to suggest, however, that the team of Webber, Schwarz and Francisco have managed to put together a thoughtful and thought-provoking exhibition that, among other things, avoids the visual creation of memory bubbles thus raising important questions about the temporality of the aftermath.

The exhibition not only creatively deviates from conventional aftermath projects by visualizing how Jewish culture comes back to life (without ignoring the legacies of the past). It also features perceptive and insightful texts and strong photographs by means of which visitors to the exhibition can start their own discourse on the transition from the aftermath to peace.

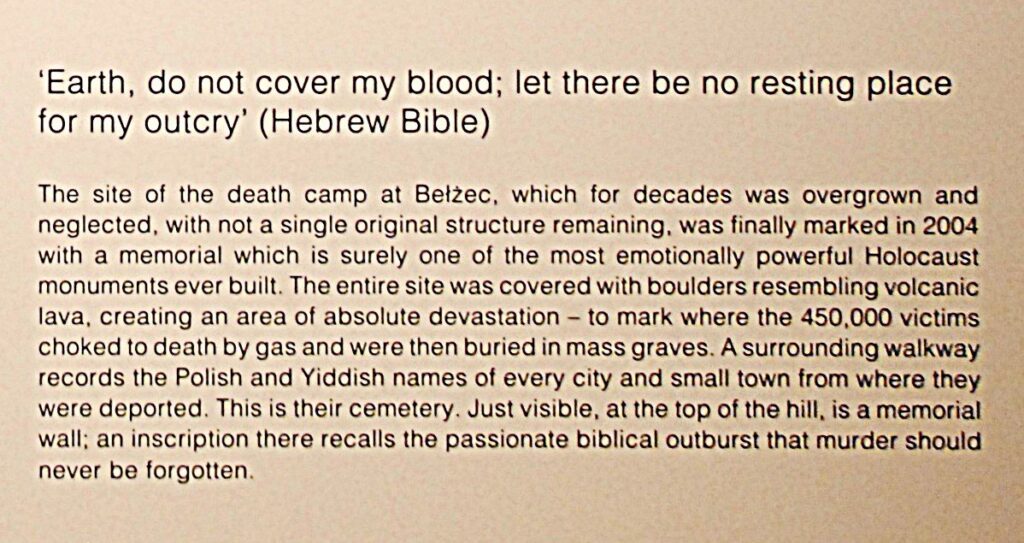

As a kind of personal visual intervention in the exhibition, we reproduce below a deliberately blurred appropriation of one of the photographs documenting the site of the former extermination camp in Bełżec. Appropriation has often been criticized but, as bell hooks noted a long time ago, “the crucial factor” is the “‘use’ one makes of what is appropriated.”³

In our earlier work, for example, we suggested appropriation as a self-critical method for visual analysis.⁴ Here, we appropriate and blur Chris Schwarz’s original photograph in an interactive process of seeing – changing – sharing⁵ to emphasize the lack of knowledge we still have about what exactly happened at this camp:

Over 450.000 Jews were murdered here. Fewer than ten people are said to have survived. Evidence of the crimes was covered up. The original structures do not exist anymore. A strictly documentary approach, we believe, would be inappropriate here, given the dimensions and the obscurity of the crimes committed in Bełżec.

More information on the exhibition can be found here.

See also:

Rediscovering Traces of Memory: The Jewish Heritage of Polish Galicia (second edition), Jonathan Webber

Photographs by Chris Schwarz and Jason Francisco

The Littman Library of Jewish Civilization, London, in association with Liverpool University Press, 2018

ISBN 978-1-786940-87-2

References

¹ See, for example, Frank Möller (2017), “From Aftermath to Peace: Reflections on a Photography of Peace,” Global Society: Journal of Interdisciplinary International Relations 31:3 [https://doi.org/10.1080/ 13600826.2016.1220926].

² See Frank Möller, “Peace Photography and the Temporality of the Aftermath,” in Picturing Peace: Photography, Conflict Transformation, and Peacebuilding, edited by Tom Allbeson, Pippa Oldfield and Jolyon Mitchell (London: Bloomsbury, 2025), pp. 47–61.

³ bell hooks (2025 [1995]), Art on My Mind: Visual Politics. London: Penguin, p. 14.

⁴ Frank Möller, Rasmus Bellmer and Rune Saugmann (2022), “Visual Appropriation: A Self-reflexive Qualitative Method for Visual Analysis of the International,” International Political Sociology 16:1 [https://doi.org/10.1093/ips/olab029].

⁵ See Audrey G. Bennett (2012), Engendering Interaction with Images. Bristol: Intellect.

Photographs taken at the exhibition for strictly documentary and non-commercial purposes.